Is China overhyped as an AI superpower?

China could be less important than you'd otherwise think. We should still regard them as a key player in the transformative AI landscape nonetheless.

Bottom line takes

Since this is a long post and I respect your time, here are my up-front takes, and — very roughly — how confident I am in them, after brief reflection.

China is, as of early 2023, overhyped as an AI superpower - 60%.

That being said, the reasons that they might emerge closer to the frontier, and the overall importance of positively shaping the development of AI, are enough to warrant a watchful eye on Chinese AI progress - 90%.

China’s recent AI research output, as it pertains to transformative AI, is not quite as impressive as headlines might otherwise suggest - 75%.

I suspect hardware difficulties, and structural factors that push top-tier researchers towards other countries, are two of China’s biggest hurdles in the short-to-medium term, and neither seem easily solvable - 60%.

It seems likely to me that the US is currently much more likely to create transformative AI before China, especially under short(ish) timelines (next 5-15 years) - 70%.

A second or third place China that lags the US and allies could still be important. Since AI progress has recently moved at a break-neck pace, being second place might only mean being a year or two behind — though I suspect this gap will increase as the technology matures - 65%.

I might be missing some important factors, and I’m not very certain about which are the most important when thinking about this question - 95%.

China is an important AI actor. I ran out of words in that sentence before I came anywhere close to running out of links making this claim.

We’re wandering through big-if-true territory here. The truthfulness of the claim that China is a heavyweight on the AI scene has, well, big implications for how we should think about governing AI’s long-term development. And while I think we should generally be sceptical about takes that pattern-match the often handwavey “okay really, [insert recent event] shows China is way ahead of the US now” talking point, I think this claim is nonetheless important to take seriously in the context of AI.

First, let me define what “important” means. In this case, I’m using it from the perspective of someone looking to steer the development of transformative AI (TAI) in a positive direction. Such a gargantuan task requires the steerer to make judgement calls about which actors to focus on, what their capabilities are, and how those capabilities might change in the future. In this sense, “important” is a fuzzy and ill-defined descriptor of where attention should be allocated, broadly speaking. Nonetheless, we’ll stick with that description to simplify the challenge of understanding China’s AI capabilities.

In essence, here are two simple statements motivating this framing:

TAI could arrive soon, and it will, almost by definition, be a big deal.

Each actor’s importance in the TAI landscape big implications for attention allocation — if we have good reason to suspect that TAI is going to be developed by actor X, we should probably focus more of our attention on governing actor X, all else being equal.

The AI landscape’s most important actors

Let’s start at a high level of abstraction. As I view it, the nebulous cloud of the most TAI-relevant actors is more-or-less comprised of Google (both DeepMind and other research teams), OpenAI, Anthropic, the US Government, the EU, and China.

The emergence of new actors will almost certainly alter this landscape. For example, Stable Diffusion, an open-sourced image generation model that made a splash in 2022, managed to achieve largely similar performance to OpenAI’s DALL-E 2 with a significantly less resourced team behind it. Indeed, it would be unwise to be overly certain that the strategic landscape will remain unchanged in the future. But for the purpose of simplification, I’ll stick with this group of actors for now.

The first three actors are pretty self explanatory: Google, OpenAI, and Anthropic are responsible for most of the exciting things we’ve seen the past few years at the forefront of AI, ranging from advanced large-language models (LLMs) capable of impressive displays of critical reasoning, such as GPT-3 and PaLM, to models that can generate breathtakingly accurate images from text inputs, such as DALL-E 2 and Imagen.

The US government, with its ever so mighty influence, is responsible for funding AI R&D, governing AI development and deployment, engaging in AI geopolitics, and playing a key role in the semiconductor supply chain, among many other social, political, and economic domains that will surely influence TAI’s trajectory.

Next we have the EU. Not typically known for producing cutting edge technical AI advancements, the EU is nonetheless likely to be an important actor from a policy point of view. This importance is mainly due in part to the ‘Brussels effect’, a phenomenon that describes how non-EU companies end up complying with EU laws and regulations.

That leaves China, broadly constructed for the purposes of this article as a combination of AI labs, research institutions, and the Chinese government (a combination of national, provincial, and local government bodies).

The rest of this article will be structured as follows:

First, I will discuss reasons to think China is an important player. Such reasons include:

China’s economic output is huge.

Important AI research might be already happening in China.

China’s AI research and development apparatus might be quite agile.

There might be quite a lot of cash floating around at the moment.

China is hedging its silicon bets by pursuing alternative computing paradigms.

Next, I will explore reasons to think China is not particularly important. Such reasons include:

China’s economic growth might slow down, and, in turn, party appetite for speculative investments in AI.

AI is not the same as transformative AI.

China has huge disadvantages with manufacturing and procuring hardware.

China’s talent needs are not being met, and there are structural factors in the way of resolving this problem.

US/UK labs might just be way ahead of China.

I then conclude by presenting my all-things-considered view, and what might cause me to change my mind.

After a rocky past, China has emerged as a force on the international AI landscape. Yet crucially, going from an ecosystem of narrow AI systems to AI that is truly transformative is uncharted territory. To better understand China’s potential to be not just a nation capable of generating economic value from various narrow AI systems, but one capable of creating world-transforming AI, we’ll need to explore the nuances of China’s current (and perhaps more importantly, future) capabilities in greater detail.

Let’s start with reasons to think China is a big deal.

Yes, they are a big deal

First, I’ll introduce a basic model of how AI is created. At a high level of abstraction, AI is the product of three inputs: computing hardware (“compute”), algorithms, and data. Specifically, present-day AI is typically the result of computing hardware executing training algorithms on large amounts of data, through a process called machine learning. Ben Buchanan at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) calls these inputs the “AI triad”, to which talent and financial capital can be added as upstream inputs that directly feed into this framework.

So, in order to create AI, you need these three ingredients in the right quantities, plus cash and talented personnel. Next, we will explore why China might be in a good position to acquire these ingredients.

Go big or go home

China is big. This can be interpreted in two different, but closely related ways: it has the world’s (soon to be) second largest population and second largest GDP. Though China’s GDP per capita is roughly that of Costa Rica, this measure is less important for thinking about China’s ability to put its economic might behind ambitious state-backed mega-projects, like building TAI. Put more plainly, Costa Rica doesn’t seem like it will be putting a rover on Mars soon, whereas China did just that in 2021.

A large GDP and population can be thought of as a massive cannon that China can strategically use to fire resources and manpower toward important economic sectors. Other details are surely important (like making sure the cannon fires properly), but don’t quite trump the fact that you have a giant cannon at your disposal. Even if you occasionally struggle to fire it, you can sometimes strike big when you do. And with over 1 billion people to tinker with the cannon, you really can punch above what your per capita GDP might otherwise indicate.

This cannon can, in theory, be used to boost strategically important sectors of the economy. While industrial policy is not always foolproof — we’ll see later how China has struggled to create a flourishing semiconductor industry despite plenty of effort — China has had some success with boosting indigenous industries. After opening their first nuclear power facility in 1991, China is now the world’s second largest generator of nuclear power, through which industrial policy was a key driver. Moreover, there’s some reason to think that AI might be particularly well suited for industrial policy. A paper from Ernest Liu of Princeton University finds that industrial policy is most effective when it targets upstream industries — ones that provide inputs to other sectors. AI seems to fit this mould: machine learning has the power to create general systems that can be applied in many economically relevant sectors

China is already doing impressive AI research

Beyond promising macroeconomic characteristics, and reasons to suspect that AI might be a good candidate for industrial policy, China is already at a reasonably strong position with respect to global AI research and development.

China is on par with the US in terms of the quantity of AI research produced. In 2021, both the US and China each published roughly 140,000 AI-related papers, together accounting for roughly 65% of the world’s total AI research output. However, quantity is not the only important factor for considering a nation’s research ability; quality is also key. A report from McKinsey in 2017 claims that “China lags behind the United States and the United Kingdom in terms of fundamental research that advances the field of AI.” Three Chinese professors noted in a critical article for HBR that, despite the rise in the volume of AI research produced in China, “truly original ideas and breakthrough technologies are lacking.”

Yet on the contrary, in a more recent report titled “Comparing U.S. and Chinese Contributions to High-Impact AI Research”, analysts at CSET note that China is not just on par with the US in terms of research quantity, but potentially research quality as well. Chinese researchers have grown their contribution to the top-5-percent most cited AI publications, reaching parity with the US in 2019 after publishing only half as much in 2010.

Analysis in 2021 by the Allen Institute found a similar trend, where China has recently taken the lead in the top 50% most-cited AI papers, and is poised to overtake the US in the top 1% in 2023. It should be noted that there is some evidence that Chinese researchers systematically cite each other more liberally, though I suspect this factor is not sufficient enough to solely explain China’s recent improvements in research output.

China’s AI apparatus

Academic research on AI is one upstream variable that feeds into the recipe for TAI, but actually making these systems is an entirely different beast. Much like we have some theoretical idea about what would happen if the Earth was instantaneously replaced with an equal volume of blueberries, we (thankfully) don’t know how to do that in practice.

To assess the “creating” part of “creating TAI”, we’ll need to take a closer look at the capabilities and track records of the most important Chinese AI actors.

First, a bit of terminology. The Chinese AI development ecosystem is markedly different from the US — therefore, I use “actors” as a catch-all term to describe anyone who plays a consequential role in Chinese AI progress. Cutting-edge AI systems in China typically come from direct interplay between government, industry, and academia, compared to the private-sector dominated approach of the US.

The mingling of these actors is the result of a deliberate strategy the Chinese government uses to encourage collaboration in the AI space. This tightly-knit apparatus could prove useful for advancing AI if strong feedback loops exist between different actors. For example, the Chinese government could find it advantageous to accelerate AI development if large models prove exceptionally useful for state interests, including mass propaganda campaigns, domestic surveillance, and/or military capabilities.

In a nutshell, private labs often work closely alongside academic researchers at top Chinese universities and government-sponsored labs such as the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence (BAAI). For example, PanGu-Alpha, a 200B-parameter LLM released in 2021, was the result of a collaboration between Huawei, Recurrent AI, Peking University, and Peng Cheng Lab, according to a forthcoming paper by Jeffrey Ding and Jenny Xiao.

Of the 22 cutting-edge Chinese large-scale pre-trained AI models analysed in this paper, half of them were trained by Baidu, Alibaba, and Huawei alone, with Tencent taking a backseat after leading the development of game-playing AI systems in response to DeepMind’s AlphaGo. Fifteen of them were in partnerships with Chinese universities, and nine included BAAI and Peng Cheng Lab.

Cash rules everything around me

Let’s talk money. China attracted around 20 percent of the entire private funds invested in AI globally in 2021, second only to the US, who attracted 60 percent. The most prominent Chinese tech companies with large AI divisions, such as Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and Huawei — hereafter referred to as BATH — posted revenues in excess of $250 billion USD in 2021, roughly equal to Google’s revenue that same year. The Chinese government has already invested tens of billions of dollars in China’s AI industry, with lofty promises for even more funding in the future. That’s a lot of cash to spend on things like hiring top scientists, buying massive compute clusters (if they’re even for sale, that is), and conducting the kind of nuts-and-bolts R&D required to train and deploy massive AI systems.

Roughly a year and a half after OpenAI’s announcement of the 175 billion parameter GPT-3 model, Baidu announced a similarly massive 260 billion parameter state-of-the-art LLM called Ernie 3.0 Titan, which outperformed other state-of-the-art models on 68 datasets containing natural language processing tasks. The number of parameters, while an imperfect measure, provides some indication of how powerful an AI system can be. Size isn’t everything, as the recent announcement of DeepMind’s Chinchilla model shows. But it’s certainly something, and China seems capable of producing big models, albeit as a laggard.

What about the future?

China has already shown some impressive capabilities with existing LLMs. But going from LLMs to TAI is a large step — and it’s one China seems keen on taking.

In an ambitious paper, called ‘Towards artificial general intelligence via a multimodal foundation model’, Chinese researchers affiliated with BAAI rather strikingly claim to have “[made] a transformative stride towards AGI”. Si Luo, the Head of the Language Technology Laboratory at Alibaba’s internal research institute, boasted that his NLP team will “explore the road to General Artificial Intelligence”.

It’s worth noting that the original Chinese term for “general artificial intelligence” probably doesn’t mean what we typically consider “AGI” in English. Nonetheless, such claims, while typically dramatically overstated, do signal some interest from influential decision makers in creating transformative AI systems with generalisable capabilities.

China hasn’t put all its path-to-TAI-eggs in a single basket. To lead the world in AI by 2030, it appears you need to diversify your AI portfolio across a variety of bets. According to a report by CSET, China is trying to create advanced AI via three different paradigms: machine learning, brain-inspired AI research, and brain-computer interfaces. Each paradigm has multiple research institutes working towards it; this report, albeit non-exhaustive, lists ten labs conducting research on each of these three potential paths to TAI.

Overall, China seems to have made some progress with existing LLMs under the popular deep learning paradigm, and looks poised to continue pushing for progress towards TAI through a variety of alternative bets.

No, they are not a big deal

I’ve spent the last few sections highlighting China’s successes and future directions that seem promising for the challenge of creating TAI. Now I will directly contrast my previous praise, and introduce new complications that threaten China’s status as a TAI hopeful.

Growth might slow if China fails to liberalise

I began my list of reasons to expect China to be a significant player in the TAI landscape by gesturing towards its gigantic economy. While that is certainly true, population and GDP alone can’t paint a complete picture of everything that matters.

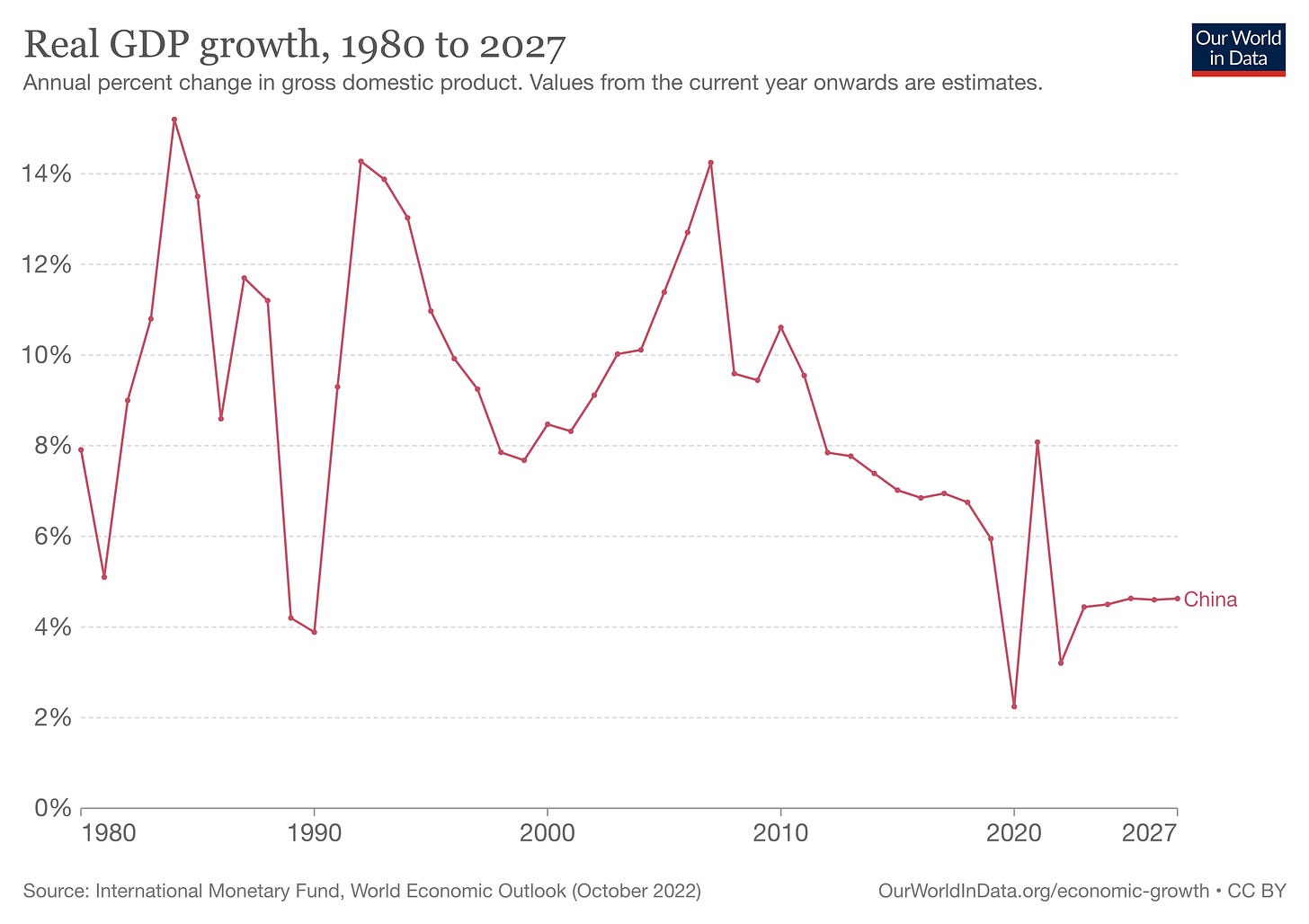

For starters, China’s growth — which is likely somewhat overstated, mind you — has already started slowing quite considerably (at least compared to its booming growth in the past). This downward trend in the growth rate is projected to continue well into the late 2020s, according to the IMF.

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, authors of the revered Why Nations Fail, describe the challenges China faces as it attempts to continue fuelling economic growth. Making use of foreign capital, technology, and markets can do wonders for a country stuck at the bottom of the economic development ladder, the two scholars argue. Moreover, the drastic increase in productivity achieved via China’s 1978 policy of Gaige Kaifang, or “reform and opening up”, allowed China to escape the dismal growth seen in Mao Zedong’s centrally-planned economy. But this type of growth might only take a country so far. Eventually, the dreaded “middle-income trap” can arrive, placing a fledgling economy in a stranglehold.

In the case of China, the growth process based on catch-up, import of foreign technology, and export of low-end manufacturing products is likely to continue for a while. Nevertheless, Chinese growth is also likely to come to an end, particularly once China reaches the standards of living level of a middle-income country. The most likely scenario may be for the Chinese Communist Party and the increasingly powerful Chinese economic elite to manage to maintain their very tight grip on power in the next several decades. In this case, history and our theory suggest that growth with creative destruction and true innovation will not arrive, and the spectacular growth rates in China will slowly evaporate. - Daron Acemoglu & James Robinson.

By and large, China’s emergence as a consequential geopolitical actor is partially due to its gigantic economy. A bigger economy generally means more money for the government to funnel into industrial policy, education, R&D, infrastructure, and the military, among other key upstream variables that are important for AI development.

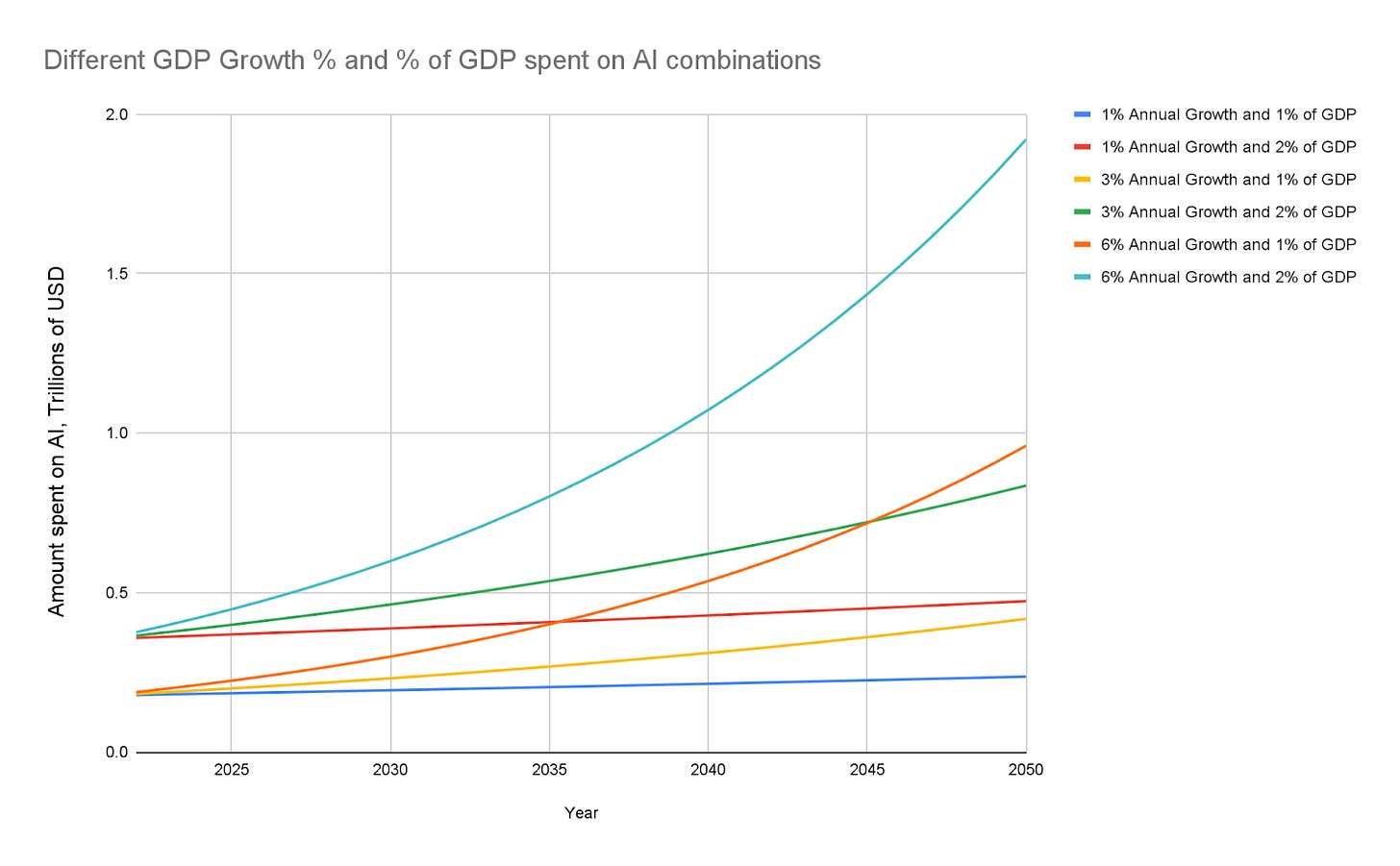

Yet crucially, a faltering economy could give the Chinese government less political leeway for speculative technological projects. Arguably, the percent of GDP that China is willing to allocate to building TAI is more important than the growth rate of GDP, at least over the next two decades or so. But if improvements to living standards slow, the Chinese government will have their hands tied with other problems that will make undertaking mega-projects like TAI more difficult to justify politically. A gigantic population means many mouths to feed, and if growth slows considerably, speculative investments like AI might see funding cuts.

AI is not the same as TAI

Let’s apply the insights from China’s growth woes to an AI-specific context. Sure, copying what US labs are doing can get China some pretty neat results. But truly pushing the envelope might be a different ball game, especially if the road to TAI is more complicated than, say, throwing a ton of compute at an algorithm doing gradient descent on large amounts of data. Orienting China’s economy around the pickings and choosings of the CCP might choke out the economic and technological dynamism needed to create TAI, and cash-rich industrial policy is not always a foolproof solution.

And ever so crucially, “AI” is not the same as “TAI”. Creating useful products and services out of computer vision models is one thing; creating truly transformative general models that are capable of a wide range of tasks is a drastically more difficult technological feat.

Highlighting the distinction between AI and TAI pours cold water on China’s supposed dominance as an AI research behemoth. Publishing a large volume of papers on highly-specialised applications of natural language processing might beef up China’s total citation count, but fundamental scientific breakthroughs in topics like deep learning might be a significantly stronger signal for a country’s odds of developing TAI.

A closer look at TAI-relevant AI sub-topics paints a far less rosy picture for China. CSET’s Map of Science, a corpus of over 260 million scientific research documents grouped into clusters, allows us to more granularly analyse different sub-topics within the AI umbrella.

The cluster on deep reinforcement learning shows that Chinese papers are cited less often than papers from other leading countries such as the US and the UK. From 2015 to 2019, only 11 highly-cited papers in this cluster were Chinese, whereas 363 were American. Citations of top papers on natural language processing with transformer architectures — a type of deep learning architecture that has been used for training cutting-edge language models like GPT-3 — has the US beating China roughly 3-to-1 in terms of average citations per paper. While China tends to specialise in applied AI topics like general-purpose computer vision and surveillance, the US is much stronger at fundamental innovations and cutting-edge research on subfields within AI that are responsible for powering the world’s most advanced AI systems.

Talent bottlenecks plague China’s AI industry

Moreover, the US dominates China not just in terms of publications, but personnel. According to a report on AI talent out of Zhejiang University, the US has twice as much AI talent as China. A closer look at top AI scholars paints an even worse picture for China. Tsinghua University's "2020 AI Global 2000 Most Influential Scholars List" shows that the US accounts for roughly 60 percent of top AI scholars, compared with China’s 8 percent. Moreover, AI researchers who received their undergraduate degrees from Chinese universities reported a greater desire to move to the US than China, according to a survey run by the Centre for the Governance of AI. These sorts of talent gaps arise from the significant hurdles China faces with fostering and attracting global talent compared to the US.

Of course, China doesn’t necessarily need to be the one innovating with clever AI architectures and algorithms to be a significant player in the TAI landscape. As ideas are typically non-rivalrous and non-excludable (once they’re made public, that is), scientific ideas can diffuse quite quickly, especially when Chinese researchers pay close attention to what their Western counterparts are publishing. This assumes that cutting-edge AI research will be published, which I suspect will not always be the case, especially as competition intensifies and firms look to solidify their positions. Nonetheless, it seems likely that, all else being equal, those who can create AI ecosystems with the best and brightest in the world will have greater importance on the global stage.

China has a Si-rious problem

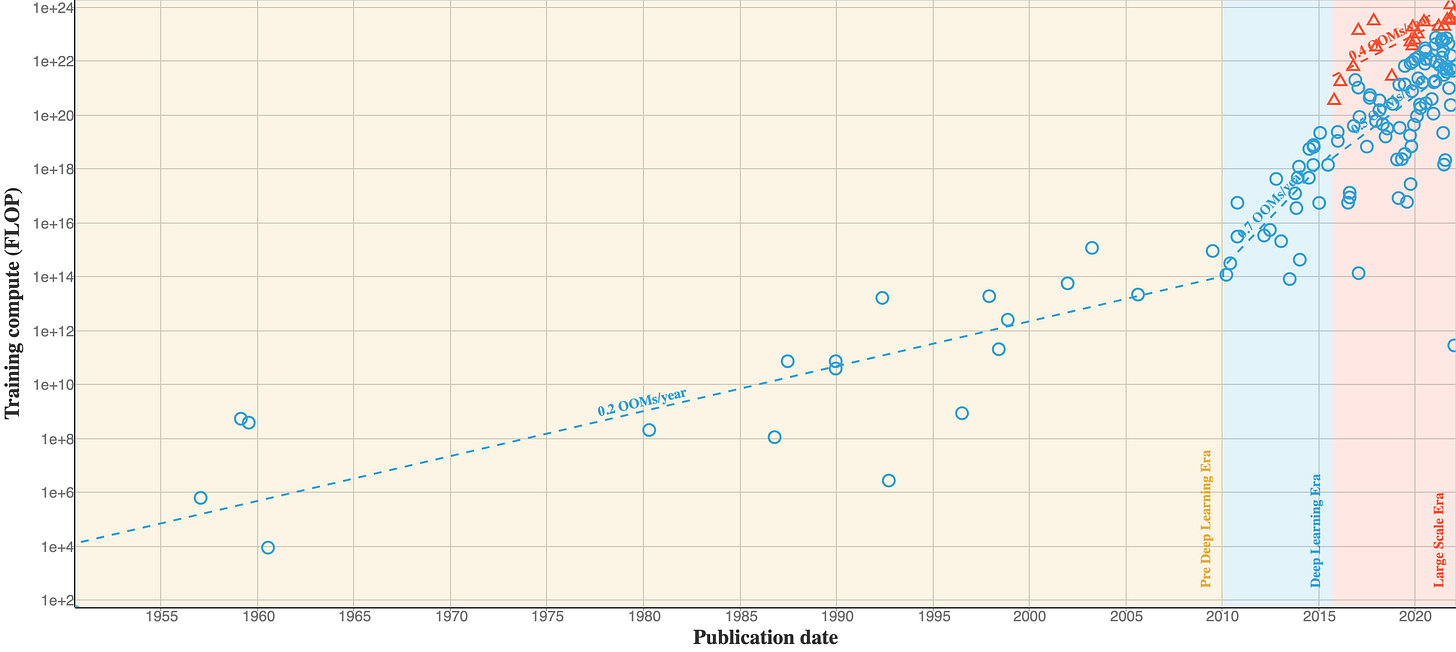

Recall from earlier that one part of the AI triad is computing power (“compute”). To create advanced AI via the current machine learning paradigm, you need a significant amount of compute to carry out the mathematical calculations needed to train large AI models. In fact, a significant amount of progress in AI has solely come from progressively larger (and thus more expensive) training runs that leverage massive amounts of compute.

These computations are typically carried out by integrated circuits, or “chips”, which are a set of electronic circuits embedded on a flat piece of semiconductor material, such as silicon. Chips are everywhere, from massive data centres used to train AI models to the phone in your pocket to your household dishwasher.

According to the current method of creating AI via machine learning, it’s currently difficult to envision someone building TAI without a significant quantity of chips, particularly the most advanced kinds. This poses a challenge for China, which is currently unable to domestically produce the advanced chips needed for training state-of-the-art TAI systems.

Si-gnificant challenges in the supply chain

China’s silicon woes largely stem from a lack of cutting-edge semiconductor manufacturing equipment (and, perhaps most importantly, the personnel needed to use it effectively), and other economic and geopolitical forces that guide the flow of chips through the semiconductor supply chain.

One piece of machinery is particularly troublesome for China. In 2020, the Trump administration successfully pressured ASML, a Dutch firm specialising in semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME), to not sell a 100 million dollar machine that is crucial for making chips to China. These extreme ultraviolet photolithography (or “EUV”) machines — which use microscopic ultraviolet light beams to print designs onto chips — are one of the most intricate pieces of technology ever made, and are crucial for manufacturing cutting-edge semiconductors. To make matters worse for China, ASML currently has a robust monopoly on EUV machines used for advanced chip production.

Even if China could make or otherwise access EUV machines (which is easier said than done), there is no guarantee they’d be able to pump out chips as effectively as firms like Taiwan’s TSMC can. After all, experienced talent is needed to successfully operate the complex tools and production processes used to make semiconductors. Tacit knowledge that rests inside the brains of chip engineers is thus a key ingredient for chipmaking. This form of knowledge is a critical bottleneck for China’s domestic semiconductor aspirations — one that cannot be unblocked through corporate espionage or well-funded industrial policy alone.

Why China might find it si-fficult to catch up

China has tried, and largely failed, to become a semiconductor powerhouse for not years, but decades. It was during Mao Zedong’s rule in the 1950s that manufacturing semiconductors was officially identified by the party as an important national scientific and technological task. Though China was “not always so behind in chip technology”, according to Jeff Ding, Mao Zedong’s purges during the cultural revolution saw top semiconductor scientists “vilified and removed from their posts”. The effects of these purges were catastrophic for China’s chip industry. In 1977, a Chinese semiconductor scientist named Wang Shouwu was quoted as saying “There are more than 600 semiconductor manufacturing plants in [China], and the total amount of integrated circuits produced in one year is equivalent to one-tenth of the monthly output of a large Japanese factory”.

Of course, China was a very poor country in the 1950s, and industrial policy failures back then might not be indicative of a radically different China’s present-day capabilities. But China had notable industrial policy failures with semiconductors as recently as the 1990s: Project 908 and Project 909, two state-sponsored projects aimed at developing an indigenous semiconductor industry in China, were nothing short of expensive failures. The former project involved seven years of bureaucracy and red tape and resulted in an inability to mass produce cutting-edge chips, and the latter cost over $2 billion in present-day USD and only managed to produce a laggard firm that only accounts for roughly 3 percent of global foundry market share today.

Nearly 30 years after these failures, firms based in just five countries and regions — the US, the EU, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan — overwhelmingly dominate the chip supply chain, accounting for 92% of the industry’s total value-add. Only the US, South Korea, and Taiwan can manufacture the most advanced chips (below 7nm), and Taiwan alone is responsible for about 85 percent of them.

Indeed, money can’t buy everything. Though the Chinese government has funnelled billions into building SME, only ASML stands at the cutting-edge of producing EUV machines. ASML’s EUV machine comprises around 100,000 parts, requires 40 freight containers, three cargo planes and 20 trucks to ship, and took over two decades to develop — it’s not exactly a DIY-at-home project.

Moreover, tacit knowledge is harder to acquire than other forms of knowledge. Barring mind reading technology, there is no way to steal it — it’s stored safely in the heads of Taiwanese engineers with decades of experience at the frontlines of chip fabrication plants. One way forward, however, is for Chinese semiconductor firms to offer cushy compensation packages to entice these workers away from Taiwan. China has managed to poach some talent from Taiwan through this strategy, but this might not be easily scalable, as Taiwanese officials have already begun implementing anti-poaching measures. Moreover, Chinese nationals working at top firms tend to return at low rates, and the return of some top talent, such as executives and lead engineers, does not solve the problem of needing tacit knowledge at the team, rather than individual level.

Past to future: sour chips, and US government’s mighty thumb

Boss Dai (戴老板), a finance blogger and a member of China’s “semiconductor investment national team”, wrote an insightful article discussing China’s lengthy history with chipmaking, titled The Sour Past of China Chips. It appears that China’s sour past has not set the foundation for a sweet future.

From 1978 to 2000, Dai argues, China’s semiconductors became “scrap metal at an extraordinary speed”, as lagging production lines quickly became inferior to those in leading-edge countries. He notes two main reasons for this failure. First, the chip industry moves quickly, leaving laggards behind in the dust. Second, Chinese semiconductor talent was too inferior to understand the complexities of chip production, let alone able to conduct the research and development needed to emerge at the front of the pack.

Dai ends his piece with a more optimistic note for China’s chip dreams, noting that the government's National Integrated Circuit Industry Fund (colloquially known as the “Big Fund”, for reasons I’m sure you can imagine), and the return of top talent, will “completely change the ecology of the semiconductor industry in China and even the world”. I’m sceptical that more and better targeted government investment, and the weak repatriation of overseas Chinese talent, will be enough to circumvent the structural hurdles that have hobbled China’s chip industry since the 1970s — hurdles which will only grow taller as cutting-edge semiconductors become even more complex, and as the US increasingly presses its thumb down on the Chinese chip industry.

Indeed, that thumb has been pressed down in recent times, and hard. In October 2022, the Biden administration announced a strict set of reforms intending to impede China’s ability to get its hands on advanced semiconductors. This multi-pronged approach broadly leverages four chokeholds to accomplish this:

Cutting off China’s direct access to the most advanced chips, such as ones designed by American firms like Nvidia.

Preventing China from accessing US-originated chip design software that is crucial for designing cutting-edge chips.

Blocking China from purchasing the equipment needed to manufacture chips themselves (and preventing existing chip manufacturers like TSMC from manufacturing advanced chips for Chinese entities that can design their own chips).

And stopping China from creating its own chip manufacturing equipment by cutting off access to essential US-built components.

To add salt to the wound, US persons (including both companies and individual citizens) are barred from supporting Chinese chip companies in efforts to develop advanced chips.

It’s hard to understate how bold these restrictions are. As CSIS’s Gregory Allen puts it: the US is strangling the Chinese tech industry “with an intent to kill”. It’s hard to concretely speculate how these restrictions might play out in the medium-to-long term — indeed, perhaps they’ll be enough to catalyse China’s semiconductor industry into becoming self-sufficient, as some have argued — though what seems clear is that the short-run effects will likely be disastrous for China’s chip aspirations. Under short AI timelines in particular, these export controls seem to have dealt a nasty blow to China’s TAI aspirations.

All things considered, China is still heavily reliant on other players in the semiconductor supply chain, such as Taiwan and the US. Though catch-up is possible — for example, Japan made impressive progress in the semiconductor market in the 1980s after being relatively weak in the 1970s — the sheer difficulty of producing top-of-the-line semiconductors might mean China is stuck well behind the US and others, at least in the short-to-medium term. This technological inferiority, alongside the crippling blow the US dealt to China’s semiconductor industry via new sets of export controls, will directly threaten China’s access to a key ingredient in the recipe for creating TAI for the foreseeable future.

Other labs are just way farther ahead

A crucial consideration for thinking about TAI’s trajectory — and in turn, its impact on the world — is who gets there first.

It isn’t exactly a secret how Google created the highly-advanced PaLM model — both you and Chinese researchers can read how they did it here. But knowing and doing are wholly different. Factors such as monstrous budgets, access to the world’s best compute, brand prestige, and top-tier talent do not diffuse as easily as ideas. You can’t copy and paste a compute cluster, nor a research scientist. And you certainly can’t snap your fingers to instantly create the ecosystem of top-tier universities, incentives to innovate, dynamic markets, high salaries, good quality of life, and other amenities that attract talent to the US from all over the world. While China has made considerable scientific and economic progress, they largely rely on domestic talent, whereas the US can access the world’s talent pool. That’s bad news for China’s significant demand for talent.

These factors are partially why, as of 2022, the jaw-dropping progress on AI mostly comes from labs such as OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic. I suspect that, all else being equal, progress at the frontier will largely come from these sorts of well-resourced actors, and the gap will widen between them and laggards even more as the technology matures. In fact, it seems reasonable to me that the current gap is even bigger than it appears. Perhaps the top labs have already trained models that are even more capable than the ones they have already released. Since China publicly lags these labs — and therefore lacks comparative prestige — the incentives for them to keep their top-tier models a secret seem weaker.

The cumulative knowledge being built inside these labs — and in turn, the large profits they will eventually reap from creating economically useful narrow AI systems — might create inertia that will be critical in pursuit of the TAI frontier. It remains to be seen whether this inertia alone will be enough to convince the AI governance community to squarely focus its gaze on the leading US labs, though it appears to me that this is a reasonable stance to take.

My all things considered view

I’ve presented arguments on both sides. But all things considered, my current view of China’s importance as a TAI hopeful can largely be boiled down to the following two bullets:

China is, as of early 2023, overhyped as an AI superpower.

That being said, the reasons that they might emerge closer to the frontier, and the overall importance of positively shaping the development of AI, are enough to warrant a watchful eye on Chinese AI progress.

It seems likely to me that the US is currently much more likely to create TAI before China, especially in the short-to-medium term. However, the original question I’m looking to answer is how important China will be. Indeed, a second or third place China that lags the US could still nonetheless be an important player, especially from a geopolitical angle. Since AI progress has recently moved at a break-neck pace, being second place might only mean being a year or two behind — though I suspect this gap will increase as the technology matures. Moreover, predictions about technological developments in the medium-to-long term are notoriously tricky. All of this points towards watching China’s progress closely in the coming years, to see if any of these structural factors (and our beliefs about their relative importance) change.

To summarise, here are the most important factors informing my view:

China’s research on the important sub-domains of AI (such as transformer architectures and deep learning) are less impressive than headlines might otherwise indicate.

I suspect China’s economic growth will slow down considerably unless its political and economic system changes in a more pluralistic direction (and even then, that might not be enough). This will make spending on large, speculative projects like TAI more difficult to justify politically, provided basic needs are not being met and growth is stagnant.

China might create interesting narrow applications of AI in domains such as surveillance and other consumer products, but this might not be enough to propel their labs and firms to the frontier.

China has a massive problem with producing compute, and the proposed solutions do not seem to be sufficient to emerge at the cutting-edge of semiconductor manufacturing.

Some of the most promising short-to-medium-term paths towards TAI will require access to gargantuan volumes of computing power, and the US government has recently taken decisive action to prevent China from accessing it.

First mover advantages are real: China is not in a great position to emerge at the front any time soon, and the most important actors from a governance point of view are probably the ones who are most likely to develop TAI first.

China will struggle with talent if it primarily relies on Chinese-born scientists, who tend to return to China at low rates. A more liberal China with higher quality-of-life might attract foreign workers, but creating such a society is not exactly easy, nor is it necessarily desirable for many government elites.

Here are some things that would cause me to update in the other direction:

China manages to avoid a huge growth slowdown, and this cumulative economic growth makes the Chinese economy truly enormous, and solidifies the CCP’s political power even further.

China begins producing leading research in important TAI sub-domains, or is able to closely follow the West. A cutting-edge algorithmic or architectural discovery coming out of China would be particularly interesting in this respect.

China’s centralised access to data gives them a massive advantage over the West and their pesky data protection laws in the long-run.

Creating narrow AI products and services for the Chinese market proves to be insanely profitable, enough to flush Chinese labs with more cash than their Western counterparts.

China solves its semiconductor struggles and begins taking a large chunk of the semiconductor market, or manages to emerge as a frontrunner in an alternative computing paradigm such as quantum computing.

Creating TAI requires less compute than previously thought, or is possible to do with the kind of inferior-generation semiconductors that China can produce domestically.

First-mover advantages are not as important as once thought, and the Chinese government can spend in an attempt to narrow the gap.

China begins repatriating researchers who go abroad at much greater rates, or manages to start attracting non-Chinese talent in considerable numbers.

The Chinese government decides to throw a much larger portion of their GDP towards AI than other comparatively sized economies, and it turns out that money can buy AI progress.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Pradyumna Prasad, Michael Townsend, Karson Elmgren, Jenny Xiao, Markus Anderljung, Fynn Heide, and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful feedback and pointers. Of course, all errors are my own.

Recently, I started reading AI Superpowers by Kai-Fu Lee, which convincingly introduces the hyper-capitalistic and ruthless Chinese business world as a deterministic ingredient to achieve AI supremacy. In contrast, this article has provided me with a much higher level of understanding by comprehensively and meticulously presenting a holistic perspective of the AI superpower race.

To what extent could most of China's AI successes be hidden from view on purpose, in the hope they are underrated as a potential AI superpower - which might give them the freedom to be more successful in their aims? Achieving an AI superpower under the radar?